The "Schrems II" Decision and Its Impact on India

- Vikram Jeet Singh

- Sep 7, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: Jul 7, 2021

- Vikram Jeet Singh and Prashant Mara

The decision of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) on July 16, 2020 upended the state of affairs for transfer of data outside the EU. The primary impact of the “Schrems II” or “Privacy Shield” ruling is on US companies, with the finding that the EU-US Privacy Shield Framework does not provide adequate protection to EU data subjects and hence the CJEU declared the EU-US Privacy Shield to be invalid. The underlying problem is that the US legislation grants the US law enforcement and US intelligence agencies far-reaching powers to access (EU) personal data, especially if the recipient of personal data is subject to laws such as the US Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). FISA permits the US government to conduct targeted surveillance of foreign persons and covers activities of electronic service providers, including technology giants such as Amazon Web Services, Microsoft and Facebook. In addition, the CJEU found that the Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) comply with the standards of the applicable European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Although the SCCs are basically held valid, the CJEU ruled that the data exporter and importer are obliged to individually examine whether a level of protection of personal data can be ensured which is equivalent to that in the European Union in terms of appropriate safeguards of the data exporter and importer, enforceable rights and effective remedies for EU data subjects.At this point, not only the contractual relations between data exporter and data importer are relevant, but also the possibility of access to the data by authorities of the recipient country and the legal system of that country as a whole (legislation and case law, administrative practice of authorities).

In other words, despite the conclusion of SCCs, there might be individual cases in which the transfer of data would be invalid as the applicable laws of the data importer, especially concerning the surveillance possibilities such as in the US, make it impossible to meet the obligations under EU data protection law. The CJEU ruled that additional safety measures might be necessary if the assessment finds that the SCCs alone do not suffice. Yet there are no clear and unambiguous findings concerning the scope of such measures under EU law.

A tangential, but no less consequential, impact of this ruling is on companies in other countries that import EU personal data. As long as the EU Commission does not declare India as providing an adequate level of data protection, any data transfer from the EU to India needs to be based on additional safeguards such as the SCCs or Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs) and hence, this ruling impacts Indian IT companies and technology providers likewise, and raises questions about the consequences of Indian Government’s data access rights.

What is the impact of Schrems II on Indian companies, or companies with operations in India?

Exports of EU subjects’ data to India are quite common, particularly where EU companies out-source their data processing to India. If EU subjects data is brought into India and stored on a server in India, the question now is whether such export and storage is in line with the Schrems II ruling.

Indian companies providing IT outsourcing or SaaS services importing EU data to process it in India.

Indian data controllers providing services to EU citizens, like multinational Indian hospitality or auto companies, holding their customer’s data, who are EU subject.

Indian IT companies who use US vendors to further process data.

Intra-group data transfer for multinational conglomerates having entities in both EU and India.

Why did the EU Court invalidate the Privacy Shield, and what this means for other countries?

The Schrems II ruling does not actually set out what level of data access or surveillance or judicial review would be acceptable under the GDPR. For any data protection framework that is not functionally identical to the GDPR,this determination will depend on the two elements that the EU Court based its decision on – government access to data and judicial review of such access. Currently, corporates are scrambling to make this evaluation for their US operations, but the same questions can logically be asked of any country to whom EU data is transferred. This specter of “Who’s next?”encourages a deeper dive into Indian data access laws. To put it bluntly, are there greater or fewer barriers to Government data access in India than in the US?

Surveillance and Data Access under Indian laws

The basic law underpinning electronic surveillance is section 5(2) of the Telegraph Act, 1885, that allows interception and disclosure of messages on the occurrence of any public emergency or in the interest of public safety. In addition to matters like state security and public order, the Government can also order this for preventing incitement to the commission of an offence.

Historically, this power was used for telephone tapping. In a 1996 case brought by the People’s Union for Civil Liberties, the Indian Supreme Court noted that telephone tapping is a serious invasion of privacy. It issued 9 rules and directions to the Government, that included a 2-month sunset on any interception orders, collection-limitation, non-retention, and an internal review committee to oversee such orders.

Following this, in 2007, a new Rule 419A was added to the Telegraph Rules, 1951, that incorporated the Supreme Court’s directions into the law. Under these rules, an interception order can be issued only when there is no other reasonable means of acquiring such information. In addition to a 2-month sunset, no interception order can be renewed for more than 6 months in aggregate.

In respect of data access, Sections 69 of the Information technology Act, 2000 (IT Act) tracks Section 5(2) of the Telegraph Act and allows the Government to intercept, monitor, or decrypt any information received or stored through any computer resource.

Similarly, and mirroring Rule 419A, the Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring, and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009 (Interception Rules). These Rules require a degree of specificity, in that allow access to any information generated, transmitted, received, or stored in any computer resource that is sent to or from any person or class of persons, or relating to any particular subject.

Is Indian law similar to US law when it comes to data access powers?

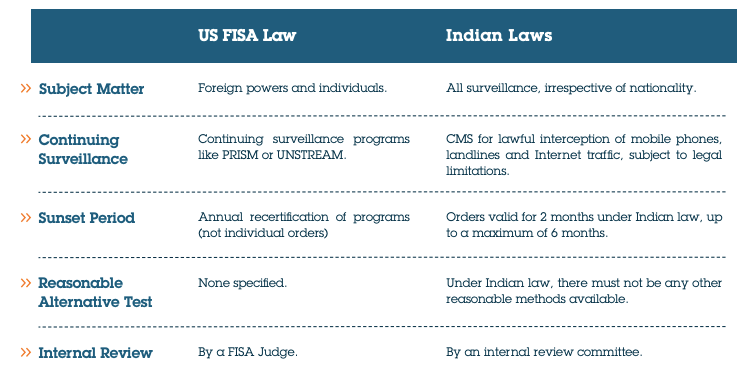

It may be difficult to predict how a EU court will answer this question, but it’s worth conducting an examination in broad strokes. There are many similarities, but also some key differences, in how Indian and US data access laws are structured.

An argument can be made that Indian law presents more barriers to unfettered data access by the Government compared to US law.

FISA allows US security agencies to carry out electronic surveillance without a court order for periods up to one year. As the name suggests, this surveillance is aimed at foreign powers or individuals, property, or premises under the control of foreign powers.

FISA does not authorize individual surveillance measures, but programs like PRISM and UPSTREAM for a period of one year. There exists a Central Monitoring System ("CMS”) operated by the Indian Government to intercept Internet and telephone traffic, but this interception and monitoring has to be in accordance with Section 5(2) and Rule 419A.

In addition, Indian data interception laws derive from earlier telephone tapping laws, which were the result of the Supreme Court’s “9 rules” set out in 1996. It can be argued that the sweep of Indian surveillance measures is lesser than FISA’s year-long authorizations, and that any such surveillance is allowed only when there is no reasonable alternative.

Indian law treats data of Indian and non-Indian citizens alike, according them the same safeguards. Elements of proportionality, time limitation, and review are also built into Indian law on account of its origin in a pro-privacy court decision.

Also to consider is the practical aspect, in that most data access requests in India are made in connection with Indian citizens’ data.A FISA-like law focused solely on foreign citizen’s data is absent.Surveillance requests are rarely (or never) made to businesses holding data for processing purposes.

What remedies are available to Indian companies or EU data subjects?

Judicial Review – The surveillance powers of the Indian Government derives from rules that (arguably) originate in the Indian Supreme Court’s 1996 anti-phone tapping judgment. There is an internal review mechanism specified in these rules, and judicial review in constitutional courts (High Courts and Supreme Court) should be possible.

Storage Abroad– The Indian IT Act has extraterritorial application, but in practical terms enforcement of orders will require routing these through MLAT procedures.Storing data in GDPR-friendly countries may be a solution.

Encryption– The Interception Rules enable the Government to require a decryption key holder to provide decryption assistance. If all, or a part of, the decryption key is located outside of India, such an order will have to be served through MLAT procedures.

Limitation– It may be possible to limit or throttle the nature and volume of EU subject’s data that is transferred to and held in India. Non-personal data or data of corporates, would be at a much lesser degree of risk from a Schrems-like finding, than personal data.

Right to Information Query- Indian citizens can file right-to-information requests with Government authorities to determine the existence or basis of certain queries. The Government can refuse such requests in (inter alia) matters relating to law enforcement, however.

Note that, unless otherwise indicated, all these measures are available to individuals (citizens or non-citizens) and legal entities.

What next steps?

Analyze and Evaluate: Your Indian operations susceptibility to Indian law data access will depend on the nature and type of data you carry. Some data is inherently more ‘interesting’ to law enforcement than others (e.g., bank records vs. health data). Evaluate what data you hold, for whom, and for what purpose. Keep a watch on proposed Indian

Data Privacy Law: Currently, data provider’s rights under Indian Privacy Laws do not align with data subject rights under the GDPR. The new Personal Data Protection Bill does import some rights from the GDPR framework, but these are counterbalanced by a number of Government access rights. That said, the law is still being formulated, and it is still possible for these data access rights to be diluted.The Indian IT industry body has already recommended that data of foreign citizens held for processing in India to be excluded from the scope of this law.

Evaluate onward data transfers: Consider any onward-transfer of EU data to the US, and also to countries who have strong surveillance regimes, in light of this ruling.

Consider additional safeguards: These can be technical, contractual, or operational, and could include data encryption, minimizing the volume of data transferred, and protocols for dealing with any data access requests from the Government.

Comments